Louise Sheridan, Senior Lecturer, School of Education

The Front Cover (or being upfront)

In the past couple of years, I finally found the time to properly focus on the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL). No more excuses that I’m too busy because of leading an Undergraduate, then Postgraduate programme – it’s been quite liberating. My modus operandi is heavily influenced by my experience as a former youth worker, which is all about participatory approaches to make learning meaningful, fun and engaging. It was about time that I did some research into the tools that I had been using, to enable me to share a fun and engaging teaching tool with my peers. The Magic Booklet (as I have named it) was introduced to me around 20 years ago by a friend. It has multiple purposes. It offers a creative medium that facilitates group discussion, it provides the opportunity for students to practice compromise and encourages students to convey ideas succinctly (or through images). Click here for a guide on how to make the booklet. Little did I know that I would still be using it to this day.

The Context (a wonderful experience, working with a group of lovely students in France)

I had the pleasure of being invited to a beautiful, small, university in France to present at an Intensive Seminar for first year students who are training to be youth, community and social workers in June 2025. A perfect opportunity to share some insights on youth participation, my concept of alfirmo (Sheridan, 2018), and test out the Magic Booklet with a group of students that I had never met. With a captive audience, and with ethical approval from the SoTL Ethics Committee, I was set to gain some insights into students’ experiences and perceptions of the Magic Booklet as a tool for learning.

The Literature (a very brief insight)

The notion of active learning (AL) is not new. However, in recent times, there has a growing recognition of the benefits of AL within the context of higher education in all disciplines. Recognising the benefits is one thing; defining AL is another. Børte et al. (2020, p.601) note a lack of universal understanding but summarise that AL involves any activities that enable students to ‘communicate, co-construct, experiment, interact, investigate, produce, and participate’ – collaboration and co-operation are key. Ribeiro-Silva et al. (2022) found, using AL can enhance student wellbeing, as well as contribute to the acquisition of graduate attributes to stand them in good stead in their future.

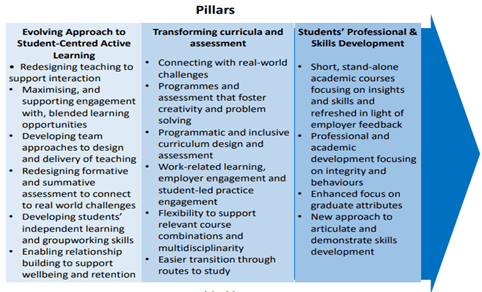

AL is a core thread within the University of Glasgow’s (2021, p.5) Learning and Teaching Strategy 2021-2025. Of note, the university recognises the imperative to:

transform curricula and assessment in ways that draw on disciplinary knowledge to address the societal challenges that we face globally, reflect our values of inclusivity, wellbeing, and sustainability, draw on best practice in teaching and assessment, and embed work-related, professionally recognised learning opportunities for students.

Three Core Strategy Pillars (University of Glasgow, 2021)

AL provides the medium through which students can build subject-specialist knowledge, as well as enhance and develop skills that are vital for their future careers and education, such as negotiation, compromise, communication, problem-solving and critical thinking. It is not enough to tell students that these are important skills, learning activities must provide the opportunity for hands-on experience and practice (Jones and Sheridan, 2025). Aston’s (2023) study found, skills in critical thinking and discussion were improved through students’ participation in AL activities. The Magic Booklet is a simple, yet effective tool that combines group discussion, negotiation, compromise and a deepening of understanding of a topic. The topic in this study was Youth Participation, but the tool could be used in a multitude of subjects/disciplines as an AL tool.

The Beginning, Middle and Back of the Booklet (an insight into what I did)

The participants were 42 students, who were just completing their first year of study on an undergraduate programme that prepares them for professional practice in community, youth and social work.

It would have been all too easy to simply give a keynote presentation about Youth Participation Practice but that is not my style – once a youth worker, always a youth worker. My visit to France presented me with an opportunity to do some SoTL. What followed was a study was about, gaining insights into the students’ perceptions and experiences of the Magic Booklet (MB) as a tool to deepen their understanding of key principles and approaches associated with youth participation.

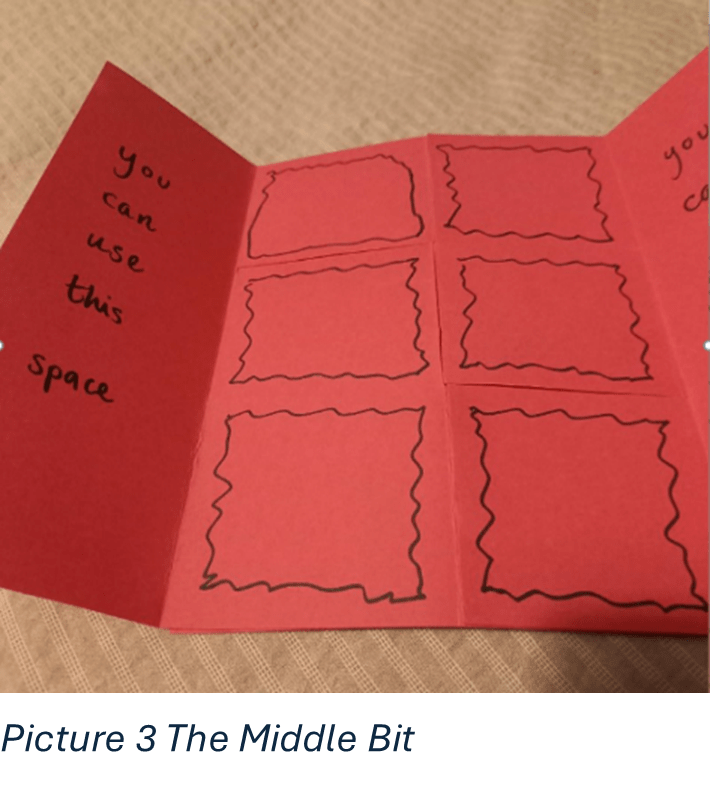

Short inputs on key concepts associated with youth participation practice, and Freirean principles (Sheridan, 2018), were interspersed with students working in groups to complete the MB. After the first input, students were assigned to groups of 4 or 5 people. By way of an icebreaker, they were invited to decorate the front cover of the MB, writing their Team name. After the second input, they discussed and noted their responses to things that they think young people find challenging within youth participation practice. Mindful that many of the students were not fluent in English, they were advised that they could write their responses in French, or they could draw pictures to convey their ideas. The crucial thing was that they stayed within the boxes (as shown in Picture 3) when capturing their responses. After the third input, they were invited to complete the back of the book. Again, working in groups, they were invited to discuss and capture the essential requirements they feel make a positive experience for young people to successfully take part in youth participation groups.

Once the back of the booklet had been filled in with words and/or images, the students thought the MB was complete. This was where the fun part came in. I asked the students if they were finished the task. ‘Oui (Yes)’ they shouted! ‘Mais non (But no)’! I replied, with some dramatic effect. Creating a sense of anticipation, I explained that they were not finished. Some students looked confused, some looked intrigued, although that might have been due to my attempt at French. Cue the drumroll….

I turned the MB over, so the front cover was facing upwards, folded it in half (lengthways) and peeled it apart to reveal the secret section…which was completely blank. Here is a video demonstration of this. As always, there was surprise and delight from the students in the room. Most had never seen this before and the two people out of 42 students did not spoil the surprise. For the final part of the activity, I invited the students to discuss and capture the implications of what they had learned about youth participation practice in the session with me for their own professional practice. Again, they worked in groups and shared ideas about what this all meant for them, as individuals and as future professionals. The final part was the act of thinking more deeply about them as professionals working with young people – as praxis (Sheridan. 2018).

Doing SoTL (a bit about the research design)

As I was interested in the students’ experiences and perceptions of using the MB, a qualitative approach was used. I used two methods to collect the data. The first method was the completion of MBs as students worked together in groups to discuss and capture their responses to 3 open-ended questions:

- What do young people find challenging within youth participation practice contexts?

- What are the essential requirements to make a positive experience for young people to successfully take part in youth participation groups?

- What are the implications for your practice – what changes might you make?

The second method was the completion of a Microsoft Form that asked open-ended questions about their experience of using the Magic Booklet to learn and engage in discussions about youth participation. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis was used for data collected through both methods. The responses found in the Magic Booklets are not captured here.

A Note on Ethics, and Limitations

As with all scholarship of teaching and learning, and research, an ethical approach is vital. I previously mentioned that the participants were a captive audience, in that all first-year students were required to take part in my presentation/session. However, I was careful to remind them that they were not obliged to participate in my study and could have opted not to complete the Microsoft Form. I was very grateful that all of them chose to do so. Ethics, for me, is doing the right things and doing things right. I have one regret, which connects to a limitation of the study. A misunderstanding on my part meant that I thought I had less time for the activity, than was the case. This resulted in parts being rushed, which does not resonate well with my usual ethics of care for participants. This is a small-scale study; therefore, I can’t make great claims based on the views of 42 people. Nonetheless, the feedback confirmed my own perceptions of the Magic Booklet, having used this within teaching many times.

Some insights (a brief exploration of some findings and key themes)

From the responses about the experience of completing the Magic Booklets, I identified the following themes, with some quotes (each from different people) for illustration purposes:

- Creative learning tools promote fun and increase engagement

| ‘It was a good experience and a new way of working for me. Our group was very cohesive and attentive. (C’était une bonne expérience et une nouvelle façon de travailler pour moi. Notre groupe a été très cohésif, à l’écoute)’. |

- Collaboration enables shared views, new insights, and personal reflection

| ‘This allowed me to reflect on these questions and introspect myself. (Cela m’a permis de réfléchir autour de ces questions, de m’introspecter)’. ‘There were exchanges between people, it was nice to know everyone’s opinion. (Il ya eu des échanges entre les personnes, c’était bien de connaitre l’avis de tous le monde)’. |

- Discussions, and the act of drawing, deepen understanding of chosen topic

| ‘It’s motivating and the questions got us to think about our professional practice. (C’est motivant et les questions nous ont fait réfléchir à notre pratique professionnelle)’. ‘The fact that the secret compartment represents questions about ‘love’ is as if we are accessing the heart of the paper. (Le fait que le compartiment secret représente les questions sur « l’amour », c’est comme si on accédait au cœur du papier)’. |

Discussion (some insights and considerations if using the MB)

Using the Magic Booklet was a resounding success. All participants had very positive things to say about their experience. The only two negative comments were that a few people wished they had more time, and one person said that stronger card should be used. The Magic Booklet is an excellent tool to enable Active Learning within Higher Education classrooms. Students used a variety of adjectives to describe the MB, cool, fun, interesting, enriching, engaging and so on. I could have simply asked the three questions noted above and got the students into small groups to discuss, but where was the fun in that. The MB added some intrigue and provided a different medium to facilitate discussions. The fact that they could capture their ideas in words, pictures or doodles heightened their engagement. This works with any group. I have previously used the MB with a group of Older People as part of a consultation for a local authority and they loved it. For that, I brought newspapers and magazines that they could cut out and stick in the MB. The golden rule remains the same – stick within the lines (or the magic won’t happen).

Using the MB enables many of the characteristics of AL, as described by Børte et al. (2020, p.601), such as promoting collaboration, shared insights, reflection. The secret section is about deepening understanding and sometimes getting students to name what are often the taken for granted ideas related to the topic. There is the option to include key information within the secret section, by printing this out, then cutting and pasting this within the lines. This would take a bit more preparation, but it might be worth it if there is vital information to convey. The secret section is about getting to the heart of the matter, as captured beautifully by one of the participants.

Dernières Pensées (some final thoughts from me)

My recommendations are that you ensure that you allow enough time for the activity. There should be time for the students to work in groups to capture their thoughts on the questions that you set (related to the chosen topic), as well as time to feedback to the wider group. This was missing in my project. It is a one-time only activity per course, or cohort of students, but it could be a core teaching activity that you use each year with great results. If you are committed to bringing the university’s learning and teaching strategy to life, to ensure an excellent student experience, why not bring a bit of magic into your classroom.

References

Aston, K. J. (2023). ‘Why is this hard, to have critical thinking?’ Exploring the factors affecting critical thinking with international higher education students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 25(3), 537-550. https://doi.org/10.1177/14697874231168341

Børte, K., Nesje, K., & Lillejord, S. (2020). Barriers to student active learning in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(3), 597–615. Available at: https://doi-org.ezproxy2.lib.gla.ac.uk/10.1080/13562517.2020.1839746

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2). 77-101.

Jones, N. & Sheridan, L. (2025) International postgraduate taught students’ perspectives on resources to support learning transitions: a preliminary case study. Open Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 4 (1) pp.142-165. Available at: https://osotl.org/osotl/article/view/122/174

Ribeiro-Silva, E., Amorim, C., Aparicio-Herguedas, J. L., & Batista, P. (2022). Trends of active learning in higher education and students’ well-being: A literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(844236). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.844236

Sheridan, L. (2018). Youth Participation in North Ayrshire, Scotland, From a Freirean Perspective. PhD. Thesis, University of Glasgow. [online]. Available at: http://theses.gla.ac.uk/9085/

University of Glasgow (2021). Learning and Teaching Strategy 2021 – 2025. [online] Available at: https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_842671_smxx.pdf

All images taken by the author